By Sue Muncaster // Photography by Bradly J. Boner

–

“The federal government is telling our teachers what to teach.”

“Education is being dumbed down.”

“It’s too hard, and there’s too much high-stakes testing.”

“We don’t have the resources; teachers will leave.”

“It’s a leftist agenda.”

As with anything revolutionary, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are highly debated. Now fully adopted in both Wyoming and Idaho, as well as in forty-two other states, the real impact of these standards will not be known for several years. And I certainly have my own opinions.

As a parent of a second-grader who transferred from Victor Elementary in Idaho to Jackson Elementary this past March, and of a freshman at Journeys School (who had spent seven years in public schools), sorting through the facts to present a coherent argument was more than just an assignment for me. It was my mission.

Education Advancement

Standards define what a student should have mastered by the end of each grade. The No Child Left Behind Law—a 2002 update of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act—required that each state adopt content standards in core subject areas. But because they were developed at the state level, the standards varied across the nation in content, rigor, and definition of student proficiency. The CCSS—spearheaded by the National Governors Association, the Council of Chief State School Officers, and a wide range of stakeholders—were developed to define a consistent, clear progression of what students should know in English Language Arts (ELA) and Math for grades kindergarten through twelve. However, cur-riculum choices and instructional methods are determined at the local level, and state adoption of the CCSS is not mandatory.

“The misperception of how the [CCSS] were set is unfortunate,” says Monte Woolstenhulme, Teton County, Idaho, school district superintendent. While much of the public thinks the standards follow a national curriculum, it’s actually the districts that plan their own strategies. “The biggest challenge was that the individual districts were initially left on their own to figure out the curriculum and assessments at a time when we were hit with major budget cuts,” he explains.

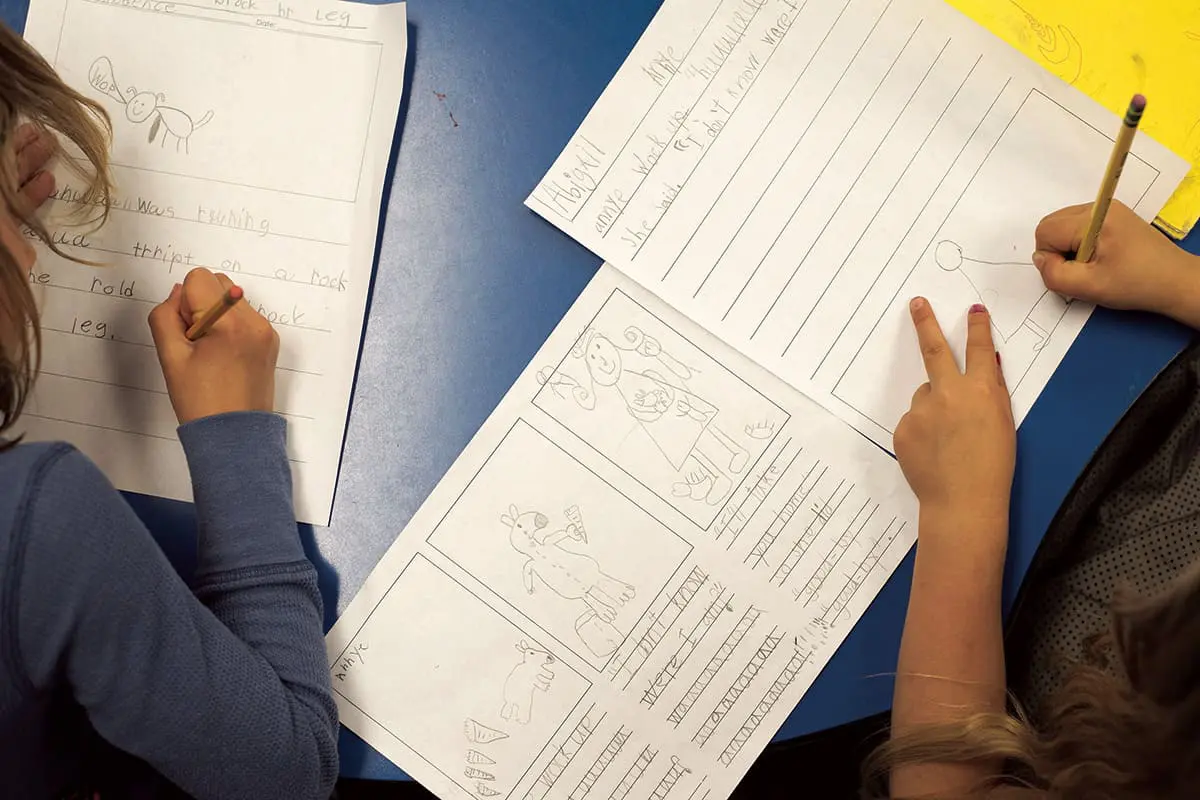

Contrary to popular belief, the intent of the CCSS is to help students become problem solvers, critical thinkers, creators, and innovators, rather than just memorizers and repeaters. Additionally, the standards insist that all teachers in all subjects share responsibility for developing students’ literacy skills. The CCSS highly support differentiated instruction. And students at different levels can choose (with teacher guidance) their own ways to learn, ways to demonstrate what they have learned, and ways to progress at their own pace. Students are also allowed to explore subjects that resonate with them, giving them ownership of their own learning.

The Big Rollout

Idaho adopted the CCSS in 2009 under the name Idaho Core Standards and began implementing them in 2013. Wyoming adopted the CCSS in July 2012, with a goal of implementation in 2014. But it wasn’t until 2015 that CCSS-aligned math was taught in Wyoming, countywide.

Curricula—the instructional methods and materials used to deliver instruction—differ, as states, districts, and schools adjust them to fit the standards. According to Teton County, Wyoming, Superintendent Gillian Chapman, “In K through five, we have specific curricula [such as Lucy Calkins for ELA and EngageNY math]. … In middle and high school, teacher teams, principals, instructional coaches, and consultants have worked to align our instructional program to the standards, which includes selecting common instructional materials as our district curriculum.” Teton County, Idaho, also uses Lucy Calkins and EngageNY math in elementary school, as well as a variety of other curricula. And at the upper levels, the district is working toward alignment in much the same way as Wyoming, with professional development workshops, resources provided by the State Department of Education, leadership networks, and direction from regional specialists. Superintendent Woolstenhulme says, “We saw a big shift in resources—teaching is no longer textbook-driven, but is structured to use a variety [of resources] to reach students, including the Internet and leveraging local community experts.”

What’s Up with the Math?

It’s the math curriculum that has caused parents and teachers the most heartburn. Every educator interviewed for this article expressed frustration over parents confusing “the curriculum” with “the standards” (which is easy to do when your kid’s EngageNY math homework says “Common Core” on the bottom).

“It’s definitely not math the way we learned it. It took a long time, but now I see how it addresses different learning styles and makes everyone understand multiple ways of getting to the same answer,” says Victor mom Janene Witherite. Another local mother, Leslie Heineman, says, “It’s a good way to pull in kids who learn from a different perspective, but for [my fourth-grade son], it gets really repetitive and boring. I worry about keeping the fire going.”

Sarah Granado, a first-grade teacher at Victor Elementary, lends her opinion: “As a student who struggled with abstract mathematical concepts, I remember complaining loudly, ‘When am I ever going to use this?’ My students will never be able to say that. They solve an ‘application problem’ each day and are even asked to write their own.”

Principal Megan Bybee of Rendezvous Upper Elementary in Driggs, Idaho, has seen a definite improvement in equity, alignment, and progression of skills that she attributes to the CCSS. “I love EngageNY,” she says. “When you look at the data, we have more students now proficient in math skills than I have ever seen. I am so excited to have kids come into school next year with a couple years of EngageNY as a baseline.”

Individual schools seem to be working out their own ELA curriculum, which concerns Teton County, Idaho, school board member Nan Pugh. “We were in the midst of budget cuts and the district was left to figure out a curriculum based on minimal training. At times, what teachers created and modified looked different in each classroom.”

Alignment and Execution

In Teton County, Wyoming, many teachers expressed a general discontent with the lack of resources, training, and direction, leaving them with the responsibility to interpret the standards and invent curriculum on their own. One teacher says, “CCSS leaves so much to interpretation, it’s hard to see how that is viable and consistent from classroom to classroom. We are scrambling for resources and have smart people who paid attention, but curriculum, so far, has been a moving target.”

Victor’s Granado paints a different picture. “When I first started teaching reading to first-graders thirteen years ago, my focus was on decoding. I felt that my students needed to be able to figure out the words and read fluently. … Deep comprehension was left to the grades above. Now, I am delighted with the intelligent way my readers think. They compare books about the same topic. They track characters in a series. … They read and talk about books in analytical ways. … Granted, this happens at different levels, but they are all expected to grow these skills.”

A major challenge for all schools is the expectation that CCSS are implemented across all subject areas. Jackson Hole High School Principal Scott Crisp explains, “By high school, we are not used to making kids better readers, but that was our school-wide goal this year across all subject areas. Aligning to Common Core means developing an ‘academic vocabulary’ and being able to identify evidence in text to justify an answer.”

And what about differentiated instruction and how the CCSS impact special-needs and English-language learners (ELLs)? Granado says, “When I switched over to a workshop model for language arts, it did wonders for my student engagement. Because students are allowed to read and write at their own ‘good fit’ level, they are not forced to endure instruction that doesn’t apply to them.”

Superintendent Woolstenhulme believes the CCSS are “driving teachers and empowering students beyond regurgitation and route learning.” When visiting classrooms, he now sees improvement. “It’s not just what you know, but how well you can share and communicate it,” he says. Granado agrees: “One [good] thing about CCSS is that the responsibility is transferred to the students to be teachers. This occurs in all subjects in my classroom now. … Today, I even watched a writing partner help revise and edit his partner’s poem.” She says ELLs and special-needs kids also take part in this “teaching” and that all students are now thriving in an environment where they feel valued.

The – Dare I Say It – Tests

Classroom and district assessments inform teachers how well students are succeeding, while statewide, or summative, assessments give a broader look at how they compare nationwide. The federal government requires all states to test students annually in grades three through eight and only once in high school in reading, language arts, and math. However, students must be tested in science once in each grade. And while none of the tests are specifically mandated by the CCSS, state Departments of Education and local districts determine which ones are given.

Idaho has joined twenty other states in adopting the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), a summative test developed by a state-led consortium. Currently available for grades three through eight, and for grade eleven, it fully aligns with the CCSS and is designed to address long-standing concerns (historically, standardized tests measured the ability to memorize facts, rather than critical thinking and applied knowledge). The SBAC is “computer-adaptive,” meaning that a student who answers a question correctly will receive a more challenging question, while an incorrect answer generates an easier one. This method is designed to provide a more engaging experience, be more time-efficient, and—especially for low- or high-achieving students—produce more accurate results. The SBAC is also designed to eliminate visual, auditory, and physical access barriers for students with disabilities, so they are essentially able to take the same test as their peers. And it provides tools to help ELLs demonstrate their knowledge, regardless of English proficiency.

The first SBAC was taken as a “field test” in Idaho in the spring of 2014. Wyoming will administer the state-developed Proficiency Assessments for Wyoming Students (PAWS) test in the 2016-17 school year, and is in the process of choosing a CCSS-aligned test that will be implemented in 2017-18. Currently, both districts use the formative test, MAP (Measures of Academic Progress). And while it’s not totally aligned with the CCSS, it’s designed to inform teachers where students are at the time of the test and to help develop growth goals and instructional strategies for the coming year. At the high school level, benchmark exams are given throughout the year, and the ACT Aspire and ACT are still the summative tests for upperclassmen.

So, How High Are the Stakes?

The “suburban mom” outcry against the CCSS is blamed on the fear that with a new system and a new way of scoring, students would not perform as well as they did historically. There is no way to compare new scores with old ones or compare states taking different tests. It’s yet to be seen if the more rigorous standards, backed by rigorous assessments, will prove the naysayers’ prediction.

I’d contend that it’s not the results or volume of testing that makes us uncomfortable, but rather the amount of time spent “teaching to the test.” Principal Bybee balks at this idea. “We don’t need to. If the tests are adequately and appropriately aligned to the standards, and we are meeting the standards, our students should do well.” She feels that the writing requirement is excessive, but understands where it comes from. “If you are expected to write twenty pages in college, you have to be able to pull off one paragraph in fourth grade,” Bybee says.

The Be-All and End-All

What do I know?

Last spring we took our family to South America for one month in January. An inch-thick packet of EngageNY worksheets (to keep our first-grader, Nico, up to date) weighed us down. But once we got the hang of it, the homework sessions began to fly by. “If I know it in a snap, my teacher says I don’t have to do all the explaining,” Nico insisted. Three weeks after returning to the Tetons, we moved over the hill and enrolled him in Jackson Elementary. His new class was within a couple weeks of the exact same math lessons, and the spelling and writing workshop processes were almost identical. This made the transition seamless.

In early April, I noticed Nico wasn’t completing the “please explain” portion of his daily math homework. “If it’s on the test, I’ll explain it,” he said.

“Do you talk about the tests at school?” I asked, knowing that the end-of-year assessments were a couple weeks out.

“Yeah, that’s pretty much all we practice,” he said. And my heart dropped.

But not ten minutes later—after he whipped through a Fly Guy book I know I couldn’t read until third grade—he started telling me the intricate plot of the story he was writing. It was about three friends who fell into a crevasse “as thick as a car” in the Alps and dug their way out through tunnels with hammers. An informal survey of his classmates was also reassuring.

Thirteen out of fourteen kids liked presenting their work to their peers, saying it made them feel proud, it was motivating, and they got to help out by being the teacher.

Locally, Teton County, Idaho, recently hired a curriculum assessment director, and both districts look forward to continued improvements for teachers’ professional development, with the sharing of open-source resources and collaboration within districts, across districts, and across the country. Many argue that the paradigm shift to deeper learning for all students will take a generation, or even more.

But is it really the curriculum, the district, the funding, or the teachers that will determine whether our students succeed?

Superintendent Woolstenhulme says (and volumes of research support this), “Of course we take ownership of quality teachers and curriculum, but the biggest factor in student success is a stable, supportive family—we can do amazing things with that partnership.”

Opting out?

Wyoming: Pursuant to the Wyoming Accountability in Education Act, districts are required to administer assessments to all students in the appropriate grade levels and may not allow students to opt out, or their parents to opt them out, of the assessments provided by law.

—

Idaho: Idaho Code 32-10-12 allows parents to make choices that affect their children’s education, and opting out is one of them. However, if a school goes below the 95 percent participation rate mandated by the federal government, it could jeopardize district funding.

Resources

Parent Resources:

What Parents Should Know about Common Core Standards: corestandards.org/what-parents-should-know

Parents’ Guide to Student Success In Common Core: pta.org/parents/content.cfm?ItemNumber=2583

Math Homework Support:

Khan Academy: khanacademy.org/commoncore

EngageNY Homework Help (videos for EVERY assignment): oakdale.k12.ca.us/ENY_Hmwk_Intro_Math

YouCubed (Stanford University): Resources for Parents: youcubed.org/parents