By Molly Absolon // Illustrations by Stacey Walker Oldham

—

Spring. As the last of the snow melts, the foothills of the Tetons and surrounding mountain ranges take on a faint green hue. Aspen leaves unfurl, shiny and new. Lawns shift from brown to a haze of green, and then—pop!—everything turns yellow as the dandelions bloom.

From their first blossoms in May or June, dandelions blanket not only the Teton area but also much of the temperate world. They are annoying to some, and persistent, but they aren’t the weeds that really cause problems.

“Noxious is a legal definition for weeds,” says Amanda Williams, the Teton County, Idaho, weed superintendent. “They are perceived to be a threat to agriculture and the environment. They cause economic harm.”

Dandelions do not meet this definition.

In fact, according to Williams, the biggest issue most people have with dandelions is that they interfere with their vision of a perfect lawn. But they don’t cause any economic or environmental impact. In fact, dandelions—which may have been brought to North America intentionally by early European settlers wanting a flower to remind them of home—have medicinal and nutritional value and can also be used to make a natural yellow dye. It just takes a different mindset to embrace the proliferating plants, according to Williams.

But a different mindset isn’t enough for noxious weeds.

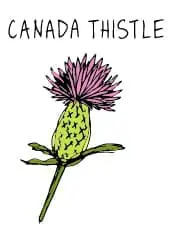

The bad ones—Canada thistle, musk thistle, spotted knapweed, and toadflax, to name a few in the Teton region—are a real threat to ecosystems and agriculture. Williams says an uncontrolled infestation of Canada thistle can reduce crop yields by up to 60 percent. It also diminishes pasture capacity, degrades wildlife habitat, and displaces native vegetation, leaving behind large mono-stands of weeds with little biological diversity and low habitat value.

Since they first plowed the land, ranchers and farmers have been fighting weeds. Invasives readily move into disturbed areas—like plowed fields, roadsides, and subdivisions—and with no natural predators or biological controls, they take over.

“The No. 1, least invasive, least labor-intensive way to stop the spread of weeds is prevention,” says Lesley Beckworth, the landowner program coordinator at the Teton County Weed and Pest District in Wyoming. “You’ve heard it: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It’s cliché. But with weeds, it’s really true.”

After prevention, the next step is what Beckworth calls EDRR: Early Detection and Rapid Response. The goal of EDRR is to control weeds before there are too many plants. At this stage mechanical removal is still a viable option.

“Our weeds program is almost exclusively chemical because of the type of work we do,” Beckworth says. “We just don’t have enough manpower to physically remove weeds from every single roadside.”

But for private landowners who own less land, chemical removal is not the only option. Intermountain Weed Control, a private company that treats invasive weeds throughout the Greater Yellowstone region, is now successfully treating infestations without the use of synthetic herbicides.

“From 2003 until 2017, we used traditional weed control, relying on chemicals and herbicides,” says Katie Salisbury, the owner of Intermountain Weed Control. “We found it wasn’t that effective, and we weren’t happy with its impact on the environment or on our employees.

“So in 2018 we switched to organic methods to control weeds—primarily mechanical removal. But you can’t just remove weeds, you need to establish something in their place or the weeds come back to the disturbed area.”

The tenacity of invasive weeds is actually fairly impressive. Most hitchhiked to North America in seed mixes, loads of hay, shipments of timber, the fur of animals, the hulls of ships or holds of airplanes, or stuck in the soles of shoes and in clothing. Many, including the notorious leafy spurge, were imported intentionally as ornamentals. Regardless, once here, they took advantage of the lack of natural controls or pathogens and took off.

“The No. 1, least invasive, least labor-intensive way to stop the spread of weeds is prevention”

– Lesley Beckworth, Teton County Weed and Pest

“There are competing theories about why invasive species are so good at adapting,” Williams says. “Native species co-evolve with pathogens, mites, fungi, viruses, and predators that keep them in check. Underground, there are complex mycorrhizal relationships that control their growth. Invasives move in and have none of these checks, so their populations explode.”

Invasives have different arsenals to ensure success. Some alter the underground mycorrhizal community. Some, like leafy spurge, can reproduce from both seeds and roots. Many weed seeds remain viable for years. And some plants can spread seeds over long distances or send taproots deep underground. All these strategies make them tough to eradicate.

“There’s job security in our business,” Salisbury says. “We are never going to get rid of all weeds, but we can manage them.

“We rely on mechanical removal followed by reseeding,” she says. “That’s what traditional spraying misses. It’s really pretty intuitive: If you remove the weeds, what’s going to grow in their place? Weeds—unless you plant something else.”

Intermountain Weed Control has created a custom seed mix with both shallow- and deep-rooted native plants to reseed areas they’ve treated. Their crews walk transects, stopping to pull and map any weed they encounter, and placing roughly 10 seeds in the disturbed area before moving on. Salisbury says that, in most places, her crews treat one acre in roughly two work hours.

“We’ve found that it doesn’t take much longer than spraying with a backpack sprayer,” she says.

Teton Valley organic farmer Sue Miller follows the same principles as Intermountain Weed Control. She prepares her beds by using silage cloth or some kind of black plastic to kill weeds before planting. Then she seeds her crop with a cover crop—often a nitrogen-fixing clover—to avoid bare ground where weeds flourish. Despite her efforts upfront, there’s still a lot of backbreaking weeding to follow. Weeds are tenacious, and if they find a weakness, they will exploit it.

Salisbury says her crews use special weeding tools that allow them to stand up to pull offenders. The tools tend to get most of the roots as well as the aboveground foliage, but keeping properties weed-free is a commitment. Salisbury says it’s just part of the responsibility of being a landowner in the West.

Because of their mandate to enforce the state’s noxious weed laws, the weed departments in Teton County, Idaho and Wyoming, continue to use chemicals in their weed treatments. “Chemicals are our bread and butter because of time and effectiveness,” Williams says. “But we work with the Bureau of Land Management and the Nez Perce Bio-Control Center for biological controls as well.”

Biological controls include the use of organisms—bugs—to act as predators on invasive species. Williams says these controls aren’t a good option for all weeds, and she warns they need to be carefully vetted to prevent the controls from turning into pests in their own right. But they do add a tool to her toolbox that allows her to manage the weeds under her purview without chemicals. Beckworth also mentions biological controls as an option her department depends upon, not so much to eradicate a particular weed but to control its growth so it can’t outcompete natives and take over. Still, the battle is never ending.

“There’s a saying in our field: ‘Our successes are invisible and our failures are obvious,’” Williams says. “It’s a continuous effort to stay ahead.”

Despite its weeds, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is relatively intact, and its weed warriors feel a responsibility to help keep it that way.

“Interestingly, Teton Valley [Idaho] has a legacy of land managed for agriculture,” Salisbury says. “Farmers and ranchers did a good job keeping weeds out. It affected their pocketbooks. But when the land was subdivided for development, that is when weeds became a bigger problem. We didn’t have the farmers out there taking care of things.”

The county weed departments and Intermountain Weed Control are resources for homeowners looking for advice and support in controlling their weeds. But for people with small yards and minimal acreage, the key—according to Beckworth, Williams, and Salisbury—is to make sure that, however you remove your weeds (by spraying or pulling), you reseed the disturbed area immediately or the weeds will just come back.

Noxious Weed Identification

—

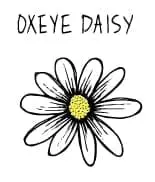

Oxeye Daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare): Oxeye daisy is a root-spreading perennial, cultivated as an ornamental, and found in some commercial wildflower seed packets. The flowers are 1 to 2 inches in diameter and consist of a yellow disk with white rays. Oxeye daisy is not readily grazed by wildlife, which allows it to aggressively invade grasslands, displacing native forage.

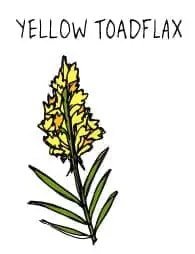

Yellow Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris): Yellow toadflax (also known as “butter and eggs”) is a creeping root perennial that spreads by both seeds and rhizomes. Toadflax can range from 6 to 48 inches high and can be found growing above 10,000 feet. It has showy, yellow, snapdragon-like flowers with an orange center and is considered a major threat to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense): Canada thistles are native to Eurasia and were introduced to North America as a contaminant in crop seed. The clustered disk flowers are purple, light pink, or white. Canada thistle is one of the most destructive species ever introduced, as it spreads through its roots and reproduces by seed.

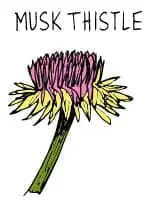

Musk Thistle (Carduus nutans): Musk thistle was introduced as an ornamental plant. This tap-rooted biennial reproduces through wind-dispersed seeds. The flower is 1.5 to 3 inches in diameter, bright pink, and nods as it matures. The plant itself stands between 3 and 6 feet tall.

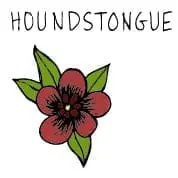

Houndstongue (Cynoglossum officinale): First introduced through crop seed, houndstongue is a tap-rooted biennial that forms a leafy rosette in its first year and flowers in its second. The flowers are reddish purple with five short petals that form clusters around the top of the plant and produce heart-shaped burr seeds. The plant is covered in soft, white hairs and is toxic to animals when consumed in large quantities.

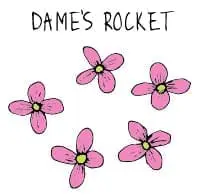

Dame’s Rocket (Hesperis matronalis): Dame’s rocket is cultivated for its attractive flowers. This biennial can grow up to 4 feet tall. The flowers are 1 inch wide and have four purple, pink, or white petals. Dame’s rocket has an aggressive root system with prolific seeds that allow it to spread quickly. It can escape cultivated gardens easily, crowding out native species.

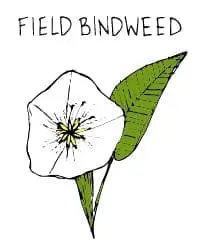

Field Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): Agriculturalists deem field bindweed one of the most noxious weeds of all. It is a climbing perennial that forms extensive root systems and reproduces through stolons, rhizomes, and seeds that can remain viable for up to 60 years. The flowers are white or pink and funnel-shaped, similar to the garden-variety morning glory flower but smaller.

Alternative Weed Treatments

—

Lawn Health

Williams says the best way to control dandelions in your yard is to keep your lawn healthy. Make sure the soil is aerated and fertilized, and mulch any clippings. Mow high and keep your mower blades sharpened. The taller the grass, the healthier the lawn, making it less hospitable to weeds.

Non-chemical, Organic Herbicides

Consumer demand resulted in the development of a number of organic herbicides, such as Weed Pharm, C-Cide, GreenMatch, and WeedZap. Herbicidal vinegar, or acetic acid, falls into this category, as well. These herbicides kill the surface plant, but don’t touch the roots, making them most effective on annuals. Use organic products when weeds are small and young—two weeks after germination. There is no residual activity, but the products are expensive and tend to work best on broadleaf plants, making them useful for treating driveways and patios.

Ground Covers

The slower but more effective way to prepare ground for planting is to kill weeds beforehand with the use of a ground cover that blocks sunlight. Black plastic sheeting, silage cloth, commercially made weed cloth, and even old nylon carpet can be used. The ground cover is typically removed once the weeds are dead; however, weed cloth can remain in place, as it allows rain and air to pass through, keeping the soil viable.

Cover Crops

Cover crops consist of low-growing plants that require little maintenance. They block light and fill disturbed areas, preventing weeds from establishing themselves. It’s important, however, to find plants that aren’t too aggressive and don’t spread too rapidly. In the Tetons, clover and alfalfa work great.

Mechanical Weeding

The crews at Intermountain Weed Control recommend a stand-up weed puller. This tool allows you to stay off your knees while weeding. The blades create a type of claw that reaches deep to remove taproots. Salisbury says her crew’s favorite models are made by Fiskars or Weed Zinger.

Play. Clean. Go.

(Stop Invasive Species in Your Tracks)

—

PlayCleanGo is an international campaign designed to stop the spread of invasive species. Launched in 2012 by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the campaign aims to give outdoor recreationalists the information and tools they need to prevent the inadvertent spread of weeds.

PlayCleanGo principles include:

—

Come Clean. Before leaving home take time to inspect clothing, boots, pets, and vehicles and remove dirt, plants, and bugs.

Leave Clean. Before heading home, inspect your belongings and vehicle and remove any dirt, plants, or bugs. In Wyoming, Teton County Weed and Pest has boot-cleaning stations at popular trailheads and hopes to install bike-washing stations as well. In the absence of such amenities, clean your gear as soon as you get home.

Stay on designated paths and trails.

Use certified or local firewood and hay. Pests can hide in firewood, and weed seeds in infested hay can blow into the environment, spreading invasives.