By Samantha Simma // Photography by Bradly J. Boner

—

Each spring, antler enthusiasts descend on Jackson Hole for what has been referred to as the “Super Bowl of Antler Hunting” during the annual shed-hunting season opener. This event draws hunters from all over the state and the country to the public lands surrounding the National Elk Refuge in pursuit of newly shed elk antlers. For many, shed hunting is more than a one-day event—it’s also a sport and a source of income—adding extra incentive to enjoy the area’s public spaces.

Simply put, shed hunting is the act of searching for, and hopefully collecting, antlers that have naturally fallen off members of the Cervidae family of mammals. These animals include elk, caribou, moose, and deer. Of these species, the males generally grow and shed antlers, although female caribou do too.

The Science Behind the Shed

Antlers are made of bone, much like an extension of the animal’s skeleton. As one of the fastest growing animal tissues on the planet, antlers may grow up to an inch per day. A new set is grown each year prior to the breeding season, or rut. Immature antlers go through a phase in which they are covered in fine hair. This hair, or velvet, provides blood supply to the bone, enabling its growth. Shortly before or during the rut, the velvet dries out and the animal rubs it off to expose a bone-like surface. The color of the antler is largely dependent on the type of vegetation the animal uses to rub off its velvet.

Antler size is directly related to the animal’s health. Healthy males produce the largest sets of antlers, as a substantial caloric intake is required to sustain vigorous growth. As the animal ages, mass is added to the structure of their antlers, so the mass of shed horns can indicate both the age and health of the animal. (A concave base, or pedicle, may indicate high levels of stress.) Unless injured, an animal’s antlers have a similar formation each year. If the antlers become damaged due to injury during their growth, a new configuration results, one which many animals retain in future grow-outs.

Once a set of antlers is fully grown, they serve as an attractant to mates, as well as a line of defense against competitors and predators during breeding season. After the rut, the male cervids experience a dramatic drop in testosterone, resulting in the breakdown of the cells responsible for antler growth. The antlers fall off naturally between December and March, depending on the region. Animals with the largest horns usually shed theirs first, and then the pedicles (the spot where the base connects to the skull) must heal. This usually takes one to two weeks, before the next set of antlers begins to grow.

When Nature Becomes Sport

The sport of shed hunting is an annual ritual for most antler enthusiasts. In earlier times, shed antlers were collected by Native Americans to be made into tools and weapons. Today, the pursuit is far more recreational, providing a unique keepsake for some, and a supplemental income for others. The highest quality antlers are often used to make furniture, décor, and jewelry. Lower quality sheds make great dog chews. Big game hunters also shed hunt to learn about the health and behavior of their prey, aiding their strategy for future hunting seasons. There’s also a large portion of antlers that are sold to buyers in Asia, where antlers are used for medicinal purposes and medical research.

The sport’s ever-increasing popularity has led wildlife and public land management agencies to regulate the collection of antlers due to illegal activity. In 2009, Wyoming’s legislature made the determination “to regulate and control the collection of shed antlers and horns of big game animals for the purpose of minimizing the harassment or disturbance of big game populations on public lands west of the Continental Divide any time between January 1 and May 1 of each year.”

A news release from the Bridger-Teton National Forest stated: “When visitors enter closed winter range, they can cause animals using the area to become stressed or flee to new locations. This retreat requires animals, especially ungulates like deer, elk, and moose, to use energy stores they need to survive. This leads to a weakened condition, which can have a direct effect on the animal’s ability to defend itself, making it more susceptible to predation and disease. Additionally, these stressors can lead to future reproduction problems which can adversely affect the overall population size.”

Timing is Everything

The exception to the winter range timeline occurs exclusively on Jackson’s National Elk Refuge. Here, an annual special-use permit obtained by the Jackson District Boy Scouts (grandfathered in during 1966) permits scouts to collect horns from the National Elk Refuge, with assistance from refuge staff members, in late April. The horns they collect are then auctioned during the annual Elk Fest, which has net over $200,000 in antler sales in recent years. Of those proceeds, 75 percent are invested back into the elk refuge, while 25 percent help fund scout troops across western Wyoming.

The National Elk Refuge—which includes 24,700 acres and is the winter home for 5,000 to 7,000 Rocky Mountain elk—might be considered the antler capital of the United States. As such, the opening day of antler season for the public has evolved into quite the spectacle. In years past, the season would open at midnight, and shed hunters armed with flashlights and headlamps would illuminate the backdrop of the refuge until the sun rose. However, incidents that included backcountry fistfights and horses being swept downriver, led to a more coordinated effort.

In 2020, the chaos of the midnight opener carried over, even though the start time shifted to noon. Confusion ensued that year, as the antler hunt technically opened at noon, but the forest service still lifted winter wildlife closures at midnight. In 2021, Wyoming Game and Fish changed the start time to 6 a.m., and the Bridger-Teton National Forest followed suit, lifting winter closures simultaneously.

Given the popularity of the shed hunt in Jackson, it has become increasingly necessary for local agencies to get involved in the regulation of the season’s opening day. The 6 a.m. opening on May 1, for lands surrounding the National Elk Refuge, has remained in place, but local law enforcement has instituted a draw system that grants shed hunters a position in a queued lineup for the Elk Refuge Road (the access point for these public lands).

During the 2022 opener, the Jackson Police Department estimated that between 250 and 275 cars joined the coordinated lineup, with nearly ten individuals in some vehicles. A similar system remained in place for 2023, a year when Teton County was the only county in Wyoming to allow shed hunting at the usual May 1 opener, whereas the surrounding counties pushed their season start date to May 15. This was a result of an emergency rule signed by Governor Mark Gordon and Ralph Brokaw, president of the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission, after evaluating the impacts of a particularly harsh winter on wildlife.

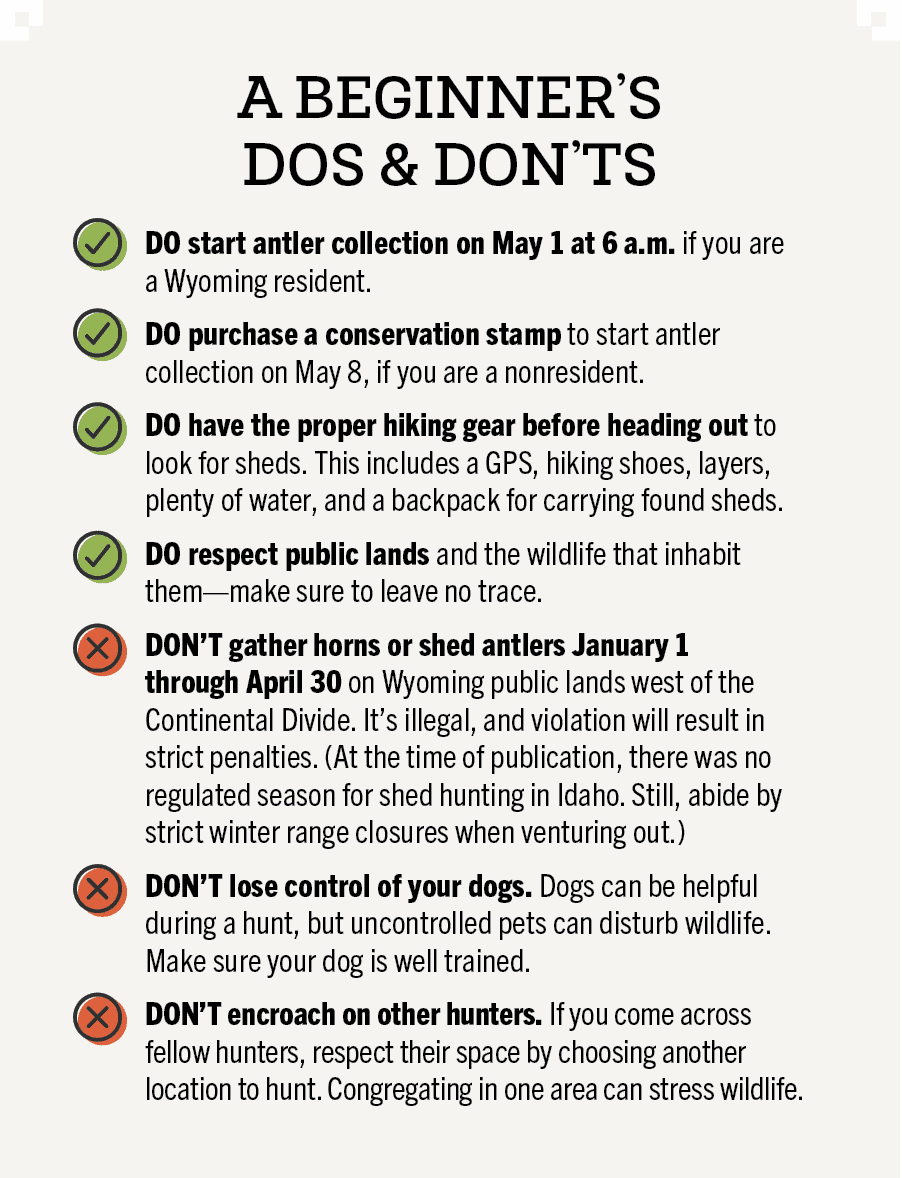

Now, for the first time, in 2024, Wyoming residents will get a head start on the hunt. Going forward, residents will be allowed to start antler collection efforts on May 1, while nonresidents will have to wait until May 8. Nonresidents will also be required to purchase a conservation stamp to legally shed hunt on public lands.