By Melissa Snider // Illustrations by Julie Millard

—

If you’ve ever stood on a podium and accepted an award for first, fastest, highest, or any other superlative, congratulations! To those remaining—the less-than-extreme dog walkers and rec-league players of the world—I congratulate you on your participation.

As a seventh-grade transplant to Jackson Hole from upstate New York, with little athletic experience, I haven’t always embraced my average athletic abilities.

At first, I hesitated to use the word “athlete” to describe my recreational pursuits. “Athlete” seems reserved for people equipped with all the gear and the knowledge and experience to use it—those who summit a peak before I’ve finished my morning cup of coffee. However, I now come equipped with my own experience and knowledge: Whether you lead the pack or stretch it out, we all have a role to play; we, the “okay-est” athletes, can inspire in our own right.

Despite growing up in a town known for its vertical feet, I never learned to downhill ski. This was partly due to the cost of the sport, and partly because I have zero need for speed. Sophomore year of high school, a friend convinced me to join the nerd-alternative to downhill skiing, the Nordic team. I reluctantly agreed, terrified of the “dryland training” descriptions I had heard through the grapevine. Little did I know, this decision would be an athletic turning point in my life.

As a newbie to the team, I understood the classic ski basics, thanks to family adventures. Skate skiing, however, was an entirely new concept and not one that my body adapted to willingly. I found myself shifting weight and nailing the glide, only to spasm into a flailing starfish and pitch sideways off the trail. All feelings of humiliation fell away (no pun intended) as my teammates became actual friends who laughed with, and sometimes at, me and always offered a hand to help me out of a snowbank.

I am a driven person who likes a good challenge, but I am not a competitive person. During Nordic races, I would sing as I skied, waving people past as they approached me—snot streaming down their faces as they maxed out their anaerobic activity, gasping “Track!” from behind. “Here comes the sun,” I’d sing to the forest, “Do, do, do, do.” I crossed the finish line serenely, nodding at my collapsed teammates, secure in the knowledge that I had done little to nothing to increase our team’s standings.

Participating in Nordic not only benefited my fitness and physical health, it provided me with new confidence and a community who didn’t care that I wasn’t a winner. This was a critical lesson to learn: I could participate at my own pace, but still be appreciated as part of the team.

Fast-forward to life in graduate school in Boston, Massachusetts. I balanced a full class load while cobbling together enough work to pay my rent—the stress was real! I deeply missed the ease of heading out my back door and up a butte. I needed to be outside; I needed to be in motion, and my only good option to get my heart pumping was something I really preferred not to do—running. When my library teacher—my mentor—invited me to run a half marathon with her, I recoiled in horror. The thought of running for that long didn’t seem possible, or fun. Still, I said “yes.”

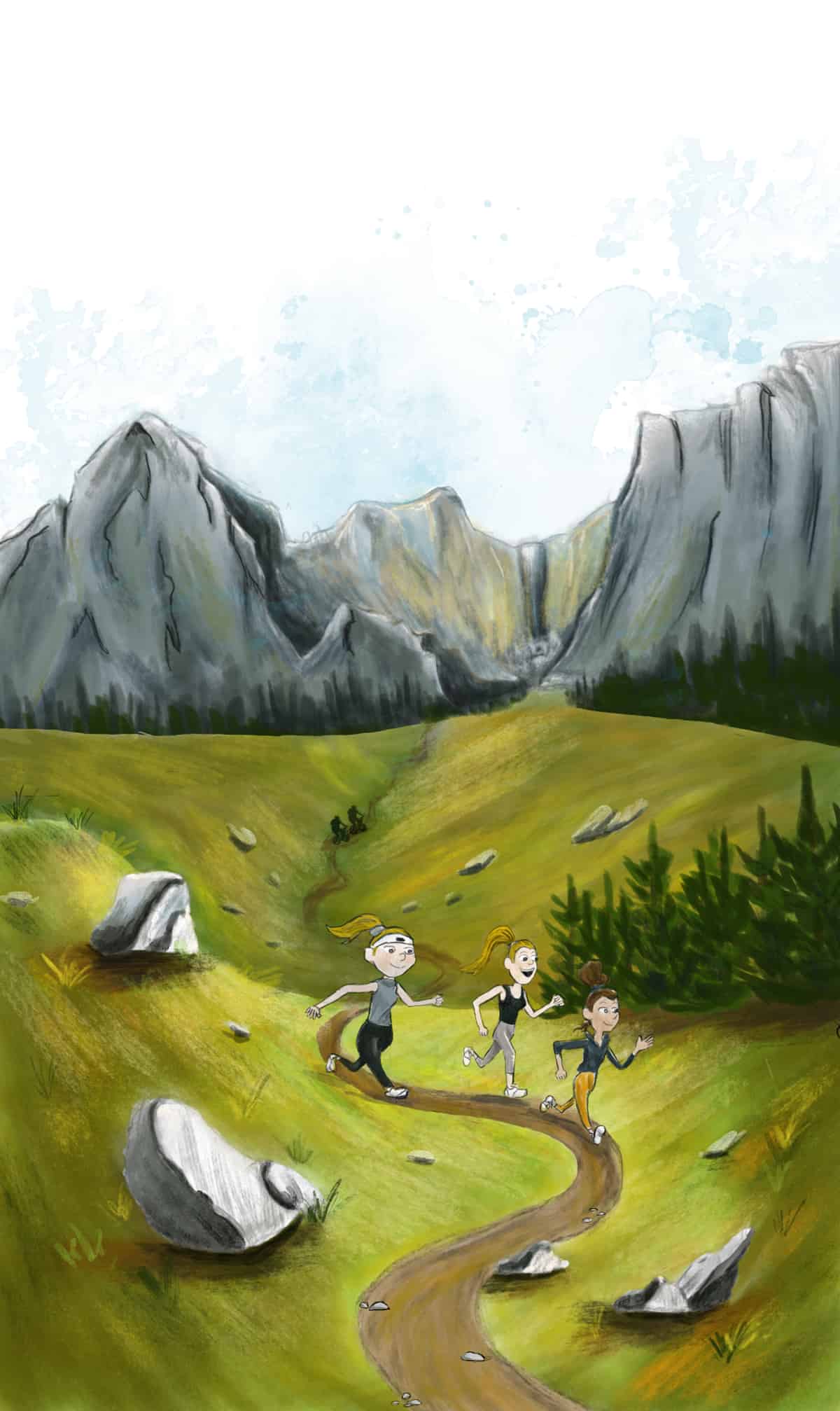

Training included long runs with other women, crunching through leaves on wooded trails outside of Boston. This was the thing I had been missing—time in nature; time with friends. It wasn’t about the running; it was about the community, the air, and the discovery of what lay beyond the next bend in the trail. I mapped city routes that took me to every reservoir and anything resembling a dirt path within 10 miles of my apartment. Exploring the city on foot made me forget life’s pressures for a while, and it felt amazing.

The half marathon circled two laps around New York City’s Central Park. I returned to Boston stiff and sore but filled with the glow of completing a goal. That was my first and final running race, but it came at the exact right moment for me.

When I met and married my husband, he thought I should give downhill skiing another chance, so we swapped disciplines. I taught him how to cross-country ski, and he taught me how to downhill. There were many times when I sat down out of pure frustration while he effortlessly tore down a run.

If you’re like me—an “okay” athlete—who also has an overactive apology reflex, you might feel like you’re holding the casually-gifted athletes in your life back from achieving more. I was often tempted to ski alone or not go at all, but enough people, who are both amazing skiers and genuine friends, led me patiently down the mountain until I started to understand why people enjoy this sport. Now I am one of those skiers who whoops when carving turns through the deep snow, but who prefers a sit-down breakfast to first tracks every time.

Just when I thought I had mastered athletic mediocrity, I experienced the joys of pregnancy and childbirth. Does taking a shower count as exercise?

We had two daughters in three years, and I entered a blur of time during which my body expanded, contracted, leaked, and hurt in new ways unrelated to vigorous exercise. My husband and I have had mixed results getting our kids outside and moving, while still finding time to be active ourselves. And it’s easy to compare us to the exceptional parent-athletes who still manage to train and compete at an elite level, and whose children now follow in their prodigious athletic footsteps. Rather than sit on the sidelines and pout, we have learned to celebrate our own victories of short destination hikes, brief ski excursions, and sometimes just playing outside on a sunny day.

Now a 43-year-old mother of two, my body is different from that of the young woman who ran a half marathon all those years ago. What does this stage of athletic “okay-ness” hold for me?

First, I take nothing for granted. I know many people who have physical limitations, injuries, illness, or other issues that prevent them from exercising in the way that they would most like to. I take that gratitude and channel it into self-compassion if I feel discouraged by my lack of speed, strength, or even motivation on any given day. Second, I feel at peace with whatever activity choice I make. I don’t compare my neighborhood walk to another person’s summit. Good for them, and good for me! I’m in it, but not to win it.

When I consider my motivations for being active right now, it comes down to community, stress relief, and rejuvenation. Sometimes it’s “forced family fun,” and sometimes it’s “me time.” I’m not without goals, and I’m willing to try a new trick here and there, but I’m really content to participate and not excel in a variety of activities.

So, whether you sing your way through a race or collapse across the finish line, there is a place for you in the pantheon of people who move their bodies. So, get out and recreate to whatever degree possible, and in whatever way brings you joy.