By Christina Shepherd McGuire // Photography by Paulette Phlipot and Rebecca Vanderhorst

—

I’m a mushroom newbie. But I don’t have mycophobia like some of my peers. In fact, in this country, mushrooms are just starting to pique mainstream interest for both culinary and supplemental use. Take for instance my Instagram feed, where ads for the hipster brand MUD\WTR pop up daily. They totally have my number, especially now that I’ve clicked on the link and discovered that this coffee substitute—a blend of chaga, cordyceps, lions mane, and reishi mushrooms—makes you feel “kinda like you took an Adderall. But not in a bad jittery way … in a super focused energized way,” as one client puts it.

Now, mainstream or taboo, I’m not after an Adderall fix, but I have to admit I wouldn’t mind feeling super focused after consuming some highly delectable mushrooms. So, being a nerdy forager myself, I tried to pick the brains of my local morel-hunting friends to no avail. They hold their stashes on lockdown, and any information given to me remained limited.

This required me to seek out the area’s real mushroom gurus, from whom I learned that both foraging for wild mushrooms and cultivating them for culinary use is as much an art as it is a science, as mushrooms—being finicky forest-floor dwellers—require precise temperatures, a specific growing medium, and an ample amount of moisture to fruit.

On the Hunt

“My favorite thing to do is go out in the woods and look down,” says local mushroom man Tye Tilt (aka Fungi Tye). “I’m always looking down. My eyes are so focused on the ground, even if I’m not out to find food.”

Tilt, owner and founder of Mountain Valley Mushrooms in Driggs, got into cultivating mushrooms after years of hunting morels with friends. “Sometimes we’d collect enough for just one meal. And then, in other years, we’d get 20 to 30 pounds.”

This sparked a business idea for the expert forager. He started selling his bounty to restaurants in Jackson in 2002. One year later, after enrolling in a grower’s course, he and partner Scott Button began to re-create indoors the wild mushroom-growing conditions he was so familiar with. They grew king oyster, pearl oyster, and shitake mushroom varieties until the production building of their farm burnt down in 2012. Since then, the partners have built the business back slowly, offering seasonal fungi varieties at regional farmers markets.

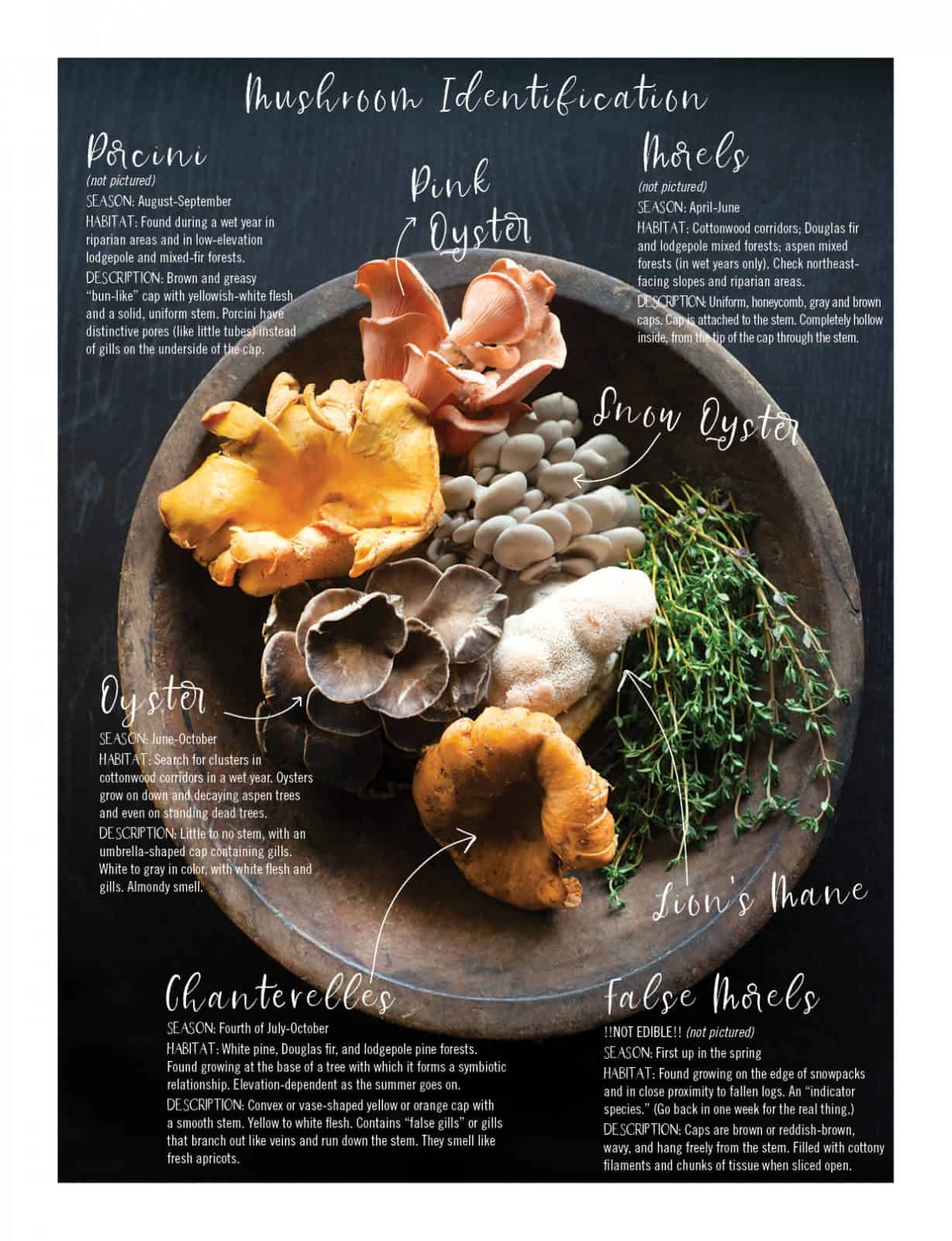

To Tilt, hunting mushrooms is like going wildflower picking: “You know your lupine. You know your arrowleaf balsamroot. And once you know your mushrooms, it’s just like hunting flowers.” He mentions that, while mushroom hunting does have a small element of risk, very few mushrooms in our area will give you more than a tummy ache, making foraging nothing to shy away from. Tilt rarely eats anything other than four local and easily identifiable species: morels, oysters, chanterelles, and porcini.

Out of the Ash

Morels—the region’s finest-tasting wild mushroom.

It’s the variety that started Tilt in the business and it’s the variety that every last one of my mushroom-hunting friends forages. I’ve eaten morels sautéed in butter and garlic, and stuffed with panko and Grana Padano cheese. I’ve sampled their honeycomb-like caps on fancy Asian dishes and searched for their elusive presence in the aspen forest on my property. Still, I have never come home with a bounty. Maybe I need to visit a burn …

“Fire morels are different,” says Tilt. This phoenicoid (a variety of fungi that fruits in response to heat) can pop up in copious bumper crops in the spring following a substantial conifer forest fire. It’s believed that Native Americans collected this edible mushroom on the regular, and maybe even intentionally set fires of their own to spur proliferation.

“A fire comes through and sterilizes the ground where the mycelium exists—they’re always there,” explains Tilt. “If you get enough moisture, mushrooms are the first thing to surface from the nutrient-dense earth. There is no competition, so they go crazy.”

Researchers believe that fire morels are a different species than the typical morchella or “true morel.” They grow in clusters and sometimes pop up in immeasurable quantities. They are bigger than the varieties found in cottonwood groves or forests, and they have an almost ashy flavor. But they are abundant and under the right conditions can grow for weeks and even months.

Best Foraging Practices

Take a stroll this spring through cottonwood corridors, conifer forests, and burn areas. Search the bases of subalpine firs or flip over the occasional dead log, and you may stumble upon edible mushrooms. Get the family involved. “Kids are low to the ground,” explains Tilt. “In a lot of cultures, kids go out [and pick mushrooms] with their grandparents, creating a lifelong passion. It can often be one of the first outings of the season.”

Whether you have kids in tow or are setting out on a solo mission, implement practices that ensure both the sustainability of the species and the viability of your hunted product:

- Always use a knife or scissors to cut the stem, rather than pulling the mushroom from the ground, so you don’t disturb neighboring mycelium.

- Never pick all the mushrooms in one area. Pick 60 percent and leave 40, then move on.

- Clean the cap on the spot with an artist’s brush. Rinsing mushrooms with water will cause them to deteriorate quickly, like a berry.

- Place your finds in a wicker basket to allow dirt and pine needles to fall through. “Putting mushrooms in a plastic bag is like death,” says Tilt. “They will rot.”

Also, follow the rules put in place by local forest districts, especially when hunting burn areas. “Fire area is delicate,” explains Mary Cernicek, public affairs officer for the Bridger-Teton National Forest. “And the sterile environment is super receptive to fertilization. You need to be hyper-vigilant about spreading noxious weeds.” She recommends washing and cleaning your equipment, including the soles of your shoes, before you go out. “These areas are ready to accept any type of vegetation and seeds.”

Playing Mother Nature

As the interest in mushrooms grows (spawned locally, perhaps, by thriving wild edibles, rather than Instagram feeds), culinary cultivators have followed the trend, reinventing wild mushroom habitats indoors. In fact, Sarah Depont and Patrick McDonnell, of Morning Dew Mushrooms in Tetonia, Idaho, are obsessed with it. By means of sophisticated infrastructure—including a sterilization room, complete with giant HEPA filters that bring in fresh air, an inoculation room where mycelium sit to “sprout” in its substrate, and a fruiting room outfitted with precise humidity and temperature control—the couple commercially grows several varieties of mushrooms and sells them to local restaurants and retailers.

Perfecting the growing substrate (one that mimics nutrient-rich soil or decaying logs) and then sterilizing it is where the fun begins. The couple builds their own mushroom filter bags (which they call “unicorn bags”) using a mix of oak pellets, made for pellet-burning stoves and shipped in from Maine, and non-GMO soy hulls. While it would certainly be more convenient to use locally produced pine pellets, most softwoods contain naturally occurring anti-fungals, making them unviable as a growing medium.

The two ingredients are mixed and bagged in an uber-clean room, and then they enter a sterilization drum to “cook” for 32 hours at 232º F. Once the bags cool, in goes the mushroom spawn (mycelium) to inoculate in another room. Then they sit to fruit in their final climate-controlled home. The whole process takes about four weeks. Due to demand, the couple is now expanding their one-year-old operation to perfect processing times.

Sampling (Culinary) Shrooms

Currently, Morning Dew Mushrooms cultivates blue, white elm, Italian, and snow oyster mushrooms, lions mane, and—the new kid on the block—chestnut mushrooms. The furry lion’s mane mushrooms were my family’s favorite. A good substitute for lobster or scallops, these dense, cream-colored beauties taste best sliced and simply pan-fried in butter or olive oil. Toast a brioche bun from 460Bread, add some crisp greens from Vertical Harvest, and, with a slather of pesto or melted butter poured over top, a beautiful vegetarian lobster roll is born. The oyster mushrooms are more delicate than their meaty counterpart, making them a perfect addition to a heavier beef dish or an egg-drop soup. Just make sure to preserve their velvety texture by not overcooking them.

The professionals do it best, however. Forage Bistro and Lounge in Driggs, Idaho, buys weekly stock from Morning Dew, particularly for use in the restaurant’s famous vegan and gluten-free mushroom cakes, with a sweet-chili gastrique. On the West Bank, Calico purchases 30 pounds a week for their grilled chicken fettuccini and other dishes. Café Genevieve and Gather take advantage of the indoor growers’ offerings around the holiday season. And Morning Dew’s oyster and lion’s mane varieties can be purchased fresh each week from the cooler inside Barrels and Bins Market in Driggs.

With permissive forest districts on both sides of the hill and hardworking local indoor farmers, there’s no excuse—even despite your possible mycophobia—not to gather some mushrooms to try for yourself. “The mushroom-picking experience is an exhilarating use of national forest,” says Cernicek. “It’s a scavenger hunt.” So why not hop on the mushroom bandwagon? (I promise I won’t disclose your stash.) If not to simply expand your palate, then for the sake of enjoying a newfound hobby.

Local Foraging Guidelines

—

- Collect up to one gallon of mushrooms a day for personal use

(in Bridger-Teton National Forest). - Collect up to 10 pounds per season for personal use (in Targhee National Forest).

- Leave no trace. Don’t drive off road. Don’t litter.

- Minimize use around trailheads and campgrounds.

- Obey stay limits in the national forest.

- Commercial permits for Bridger-Teton picking, if offered,

are available at fs.usda.gov/detail/btnf under “passes

and permits.” - Commercial permits are not currently available for Targhee National Forest.

- Foraging mushrooms is not permitted in wilderness areas.